There is an old legend that Lake Superior’s icy temperature stays cold even in the summer because of all the souls who perished in its waters. While several factors determine the Lake’s temperature, the legend is believed by many because of several famous Lake Superior Shipwrecks like the Edmund Fitzgerald. Ever heard of them? Learn about some of the most well-known shipwrecks below before visiting the coastline yourself.

There are over 6,000 shipwrecks in the Great Lakes, having caused an estimated loss of 30,000 mariners’ lives. It is estimated that there are about 550 wrecks in Lake Superior, many of which are still undiscovered. According to the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum, over 350 of those shipwrecks have been found so far. At least 200 lie along Lake Superior’s Shipwreck Coast, a treacherous 80-Mile stretch of shoreline with no safe harbor between Munising and Whitefish Point. A visit to the graveyard of the Great Lakes promises haunting reminders of the lake’s fury and the lives perished in the aftermath.

The famous Edmund Fitzgerald lies just 15 miles northwest of Whitefish Point. Perhaps the most famous Lake Superior shipwreck, has been immortalized in legend and folk song thanks to Gordon Lightfoot.

November is referred to as "The Month of Storms" on the Great Lakes. The 1975 storm that hit when the Fitzgerald went down was one of the biggest — and the worst — that Captain McSorley said he had ever seen. Winds as fast as 45 knots were reported, with waves as high as 30 feet. Both water pumps on the Edmund Fitzgerald were damaged, and the lifeboats were destroyed by the force of the strong storm.

While it is often portrayed that ships were happy to return to the water in search of Fitzgerald that night, they were not. Though they were eager to help their friends, it was a hard decision to make. Crews had to make a choice to risk their lives in hopes of saving others, or staying sheltered by the safety of Whitefish Point. While no one knows for sure the exact cause of the Edmund Fitzgerald's demise, it is certain the storm was a major factor. Waves high enough to sweep across the deck — making it too dangerous to stand there — meant the Edmund Fitzgerald was taking on water early in the day on November 10. Whatever the cause of the wreck itself, the storm that day will never be forgotten by Great Lakes sailors. Today, you can see the recovered, 200-pound bronze bell from the ship at the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum.

Stop by the Lake Michigan park along U.S. 2 to learn about the SS Carl D. Bradley, which was shipwrecked on November 18, 1958. The self-unloading freighter was the second-largest steel freighter on the Great Lakes at the time. It was upbound on Lake Michigan when a vicious November storm broke her hull in two. She sank 12 miles southwest of Gull Island before the crew could launch the ship’s life-saving boats. Of the 33 men onboard, only two survived. They were rescued at daybreak by the crew of the Charlevoix Coast Guard cutter Sundew.

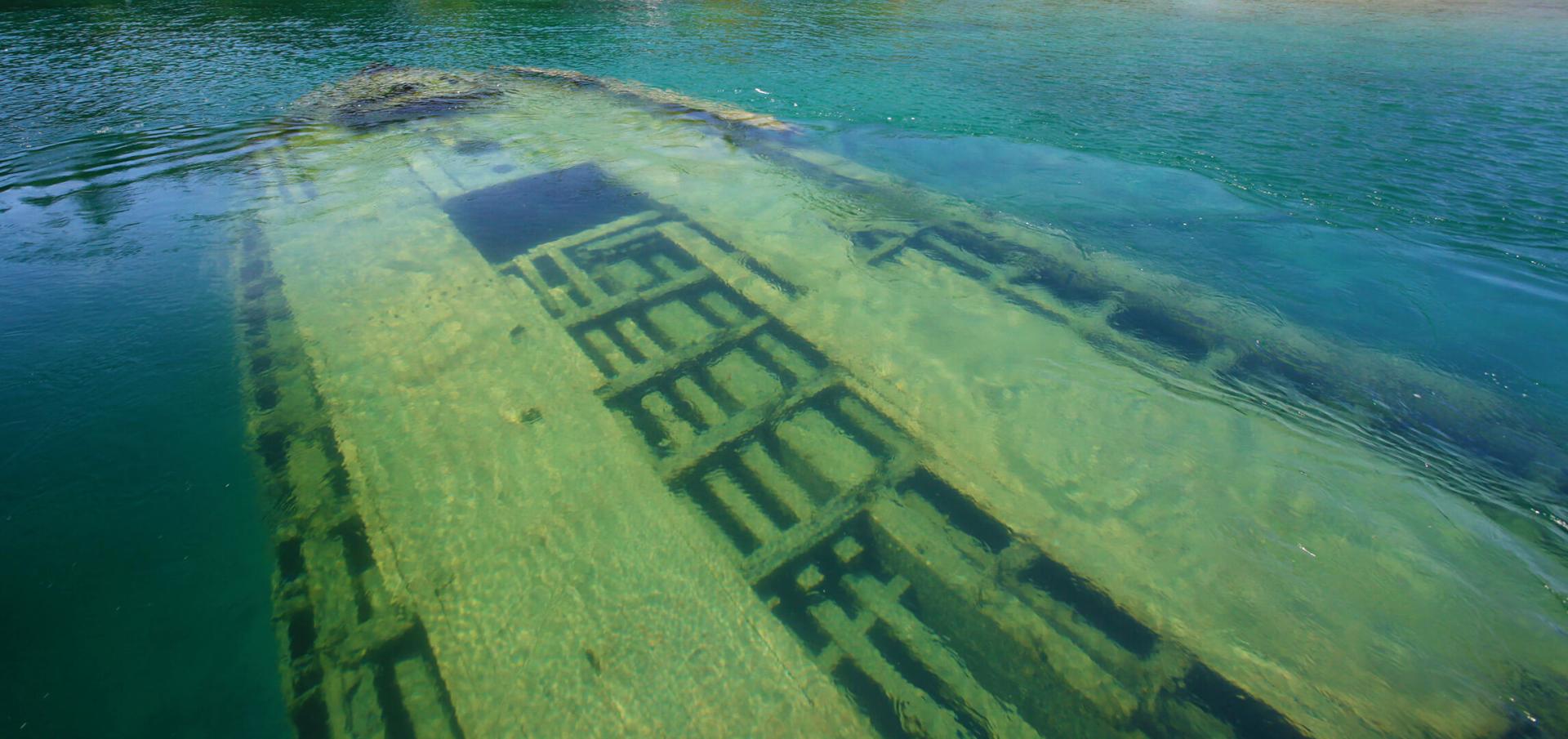

The SS Emperor struck Canoe Rocks on Isle Royale on June 4, 1947. It was the first deadly Lake Superior shipwreck since 1940. It sank in 30 minutes, taking 12 crew members with it. The Emperor’s wreckage lies partially in shallow waters and has become a popular site for recreational divers, who investigate the tragic site preserved by Lake Superior’s chilly depths.

The SS Rouse Simmons sank in Lake Michigan near Two Rivers, Wisconsin, in November 1912. This 42-year-old three-mast schooner was very old by any ship’s standards. When it left Thompson Harbor near Manistique on November 22, it was loaded with 5,500 U.P. pine trees bound for sale in Chicago. Captain August Schuenemann warmly welcomed local lumber workers aboard, inviting them to join the crew so they could visit family and friends in the Chicago area for the Thanksgiving holiday. Tragically, 16 men lost their lives to the big lake’s fierce gale-force winds.

The SS D.M. Clemson was a 468-foot-long, steel-hulled Great Lakes freighter that went missing on December 1, 1908, on Lake Superior. The ship was last seen coming through the Soo Locks onto Lake Superior. The ship was built in 1903 for the Provident Steamship Company. The wreck of D.M. Clemson is still missing, and the cause of her sinking remains a mystery to this day as there were no survivors to share the story of the ship. However, for weeks, debris and some bodies from the 24 crew members washed ashore from the ill-fated ship between Crisp Point and Grand Marais. One of the bodies found was the body of the Clemson's watchman, Simon Dunn of Dublin, Ireland, which washed ashore at Crisp Point. Dunn was wearing a life jacket with D.M. Clemson written on it. Later, pieces of the ship's cabin, 23 of the ship's wooden hatch covers and at least three more bodies were seen floating further west. Only one other body was recovered, and was identified as second mate Charles Woods of Marine City, Michigan.

Around 7:45 p.m. on October 11, 1907, in darkness and rolling seas, the Cyprus suddenly rolled to port, turned turtle and started sinking. Four men, a wheelsman, a watchman, the first mate and her second mate Charles Pitz, managed to board the ship’s emergency life raft originally located behind the pilothouse. For the next six hours, the men hung on. In frigid, violent seas, they began to encounter breaking waves near the shore.

The raft turned over and over four to five times, and all managed to get back aboard. Finally, close to the beach, the raft turned once more, but this time, only one of the frozen, exhausted men stayed with the raft. Charlie Pitz wasn’t able to climb back on, but he had tied himself to the raft, and held on until he reached shallow water, stumbling literally half-dead to a spot where he collapsed unconscious on the beach. Pitz would have died of exhaustion and hypothermia in a very short time – but he had landed just half a mile east of the Deer Park Life-Saving Station.

Here is an excerpt from the Deer Park Station’s Wreck Report for that day:

State of wind and weather: North / high / raining

State of tide and sea: No tide, sea high

Time of discovery of wreck: 2 a.m.

By whom discovered: Surfman Ocha

Time of arrival of station crew at wreck: 2:30 a.m.

Twenty-two men were not as fortunate as Pitz; their bodies washed ashore over the next couple days. Pitz revived over several hours and assisted in identifying his fellow crew. All had life jackets bearing the name Cyprus, and all but two were eventually found east of the Deer Park Life-Saving Station.

The story of the Cyprus is just beginning to be told. Her story first ran in the Winter 1999 issue of Shipwreck Journal, followed by another story written by Pitz’s great-niece, Capt. Ann Sanborn of the U.S. Maritime Service, also known as the merchant marine. Capt. Sanborn is an admiral attorney, master mariner and associate professor at the United States Merchant Marine Academy in Kings Point, New York. She has been notified of the discovery and plans to visit the Shipwreck Museum very soon. She, as well as Great Lakes author Fred Stonehouse, have compiled much information on the Cyprus.

Charlie Pitz went back to sailing immediately and did not openly discuss the loss. He did not list the Cyprus on his sea service resume provided to Great Lakes Shipwreck Historical Society by Capt. Sanborn. What caused the sinking of the Cyprus? At the time, mariners were suspicious of the new type of Mulholland sliding hatch covers – but Capt. Sanborn explains that building of the Cyprus was interrupted by a serious labor riot in Lorain, Ohio, that could have led to basic construction flaws in the vessel.

This is one of the Great Lakes’ most haunting mysteries. The SS Bannockburn was known as “The Flying Dutchman of the Great Lakes.” It sank on November 21, 1902, with no trace of its crew or wreckage ever recovered. But tales of ghostly apparitions live on, as sailors have reported sightings of the vessel’s shadowy figure amidst the fog near Whitefish Point.

The SS Western Reserve, the first major steel-plate freighter built for the Great Lakes (1890), sank during mild gale winds on August 30, 1892. She rests about 60 miles northwest of Whitefish Point and 35 miles northwest of Deer Park. The ship’s two yawls carried the 27 people onboard, including the ship’s owner, Captain Peter Minch and his family. Overloaded, both yawls capsized, killing all but one, wheelsman Harry W. Steward, who swam to a desolate stretch of shoreline between Grand Marais and Deer Park.

Based on Steward’s recounting of the deadly accident, it was concluded that the ship broke in two because it was constructed with brittle steel contaminated with phosphorus and sulfur. This led to the creation of new laws for testing steel used in shipbuilding.

Since then, there have been reports of ghostly apparitions of the Western Reserve in Lake Superior off the coast of Deer Park. Stand along the sand-gravel beach near Deer Park on a warm, calm night and you may hear voices and laughter across the lapping waves.

The SS M.M. Drake was a wooden bulk freighter that sank on October 6, 1901, near Vermilion Point on Lake Superior. It went down after colliding with the Michigan, the freight barge it was towing, which had begun to founder in a fierce storm. The Drake rescued the Michigan crew, but in the raging water, the barge raked across the length of the freighter. The after-cabin was fractured, and the tall smoke stack was lopped off and flung overboard; the ship was mortally wounded. One life was lost, but the remaining crew of the Drake and Michigan were saved by the Northern Wave and Crescent City and brought back to shore.

The Drake’s rudder, anchor and windlass were illegally removed from her wreck site in the 1980s. They are now the property of the State of Michigan. The rudder is currently on loan to the Great Lakes Shipwreck Museum, while the anchor and windlass are displayed at the Whitefish Township Community Center. The Drake is protected as part of the Whitefish Point Underwater Preserve.

Plan your trip today to the museum and coastline, where you can see artifacts and historical accounts from these shipwrecks and more.

Curious where Michigan’s closest Great Lakes shipwrecks lie near Tahquamenon Falls? Explore the tragedies off the coasts of Lakes Superior, Huron and Michigan with this interactive app.

While you can tour the Shipwreck Museum’s various buildings across its campus, you can also take multiple glass bottom shipwreck tours from different cities along Lake Superior’s coast.

Tahquamenon Country makes an ideal base camp for discovering some of the U.P.’s most awe-inspiring natural wonders, heroic rescue stories and the heartbreaking legacies of ships lost to our mighty freshwater seas. Start planning your visit today, then book a stay at nearby lodgings with the comfort and amenities you need to rest for tomorrow’s exciting adventures.

Photo Credit: Upper Peninsula Travel & Recreation Association